Doesn’t it seem that the questions after a talk are mostly asked by men? In 2014, right before the 223rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), my collaborator Jim Davenport created a quick web form so conference attendees could track the gender of speakers and those asking questions. Over the next five years, Jim, Stephanie Douglas, myself, and many others worked to disseminate the form, track the gender of those asking questions, and analyze the data. I led the analysis on two papers concerning this project, and a few more were led by others.

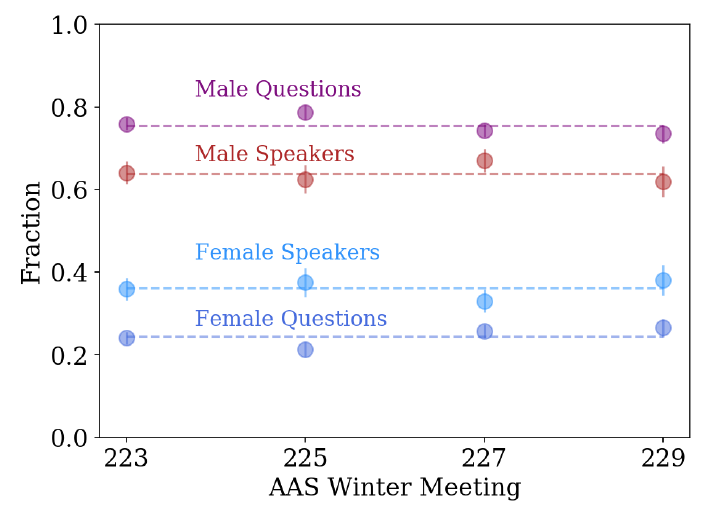

Over the course of dozens of conferences across Astronomy and in a few other fields, we found that the fraction of women who ask questions typically lags 10% behind the fraction of women in attendance. These results are shown below for four winter AAS meetings. At these and other conferences, either women aren’t asking enough questions, or men are asking too many.

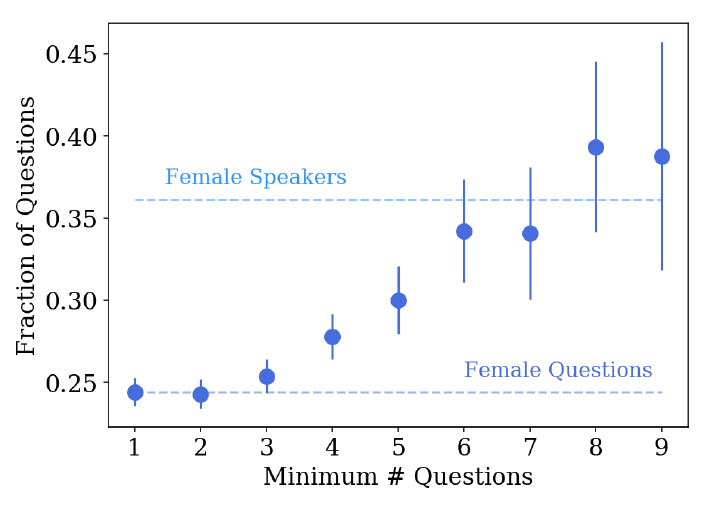

We looked for correlations between the fraction of women asking questions and gender of the session chair, the gender of the speaker, or the size of the meeting, and found these to be weak at best. The fraction of women asking questions did increase with the total number of questions per talk, indicating more women participate when there is more time allowed to do so.

Left: The fraction of male and female questioners and speakers/attendees at four successive winter AAS meetings. In addition to the data from individual meetings (with Poisson uncertainties shown), the mean for all four meetings is indicated (dashed lines). The results from individual meetings show no significant change over four years.

Right: The fraction of questions asked by women as a function of the total number of questions asked during the session. For sessions with three to five questions, the fraction increases, and in sessions with six to nine questions, the fraction of questions from women is consistent with that the fraction of female speakers/attendees at the conference.

Over five years of data collection and analysis, we were able to quantify a previously untracked gender disparity, but we ended this phase of the project in Winter 2019. We no longer endorse the use of our web form for gathering data. The web form was deployed with buttons for M/F, reinforcing the gender binary. Additionally, as the survey became more popular, it caused harm to scientists (including, but not limited to, scientists outside the gender binary) who prefer to interact scientifically without being aware that observers are labeling them with a gender. We released this statement to apologize and announce the end of the survey.

Where do we go next? It is still important that public scientific interactions include all members of our community, especially those who are marginalized due to gender or along any other axis of identity. I am eager to learn more about scientific interactions at conferences and experiment with new ideas and paradigms to support more inclusive conversations. Based on what I’ve learned, a next generation of the survey would:

- involve consultations with trained sociologists

- collect demographic information only by self-identification

- anonymously link conference attendees to their information

- actively test alternatives to traditional question sessions

If you’re interested in being part of a new phase of the questions project (especially if you have time and funding), please get in touch!

-

The Role Of Gender In Asking Questions At Cool Stars 18 And 19

S. J. Schmidt, S. Douglas, N. M. Gosnell, P. S. Muirhead, R. S. Booth, J. R. A. Davenport, and G. N. Mace

In 19th Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stars, Stellar Systems, and the Sun (CS19), Dec 2016

We examine the gender balance of the 18th and 19th meetings of the Cambridge Workshop on Cool Stellar Systems and the Sun (CS18 and CS19). The percent of female attendees at both meetings (31% at CS18 and 37% at CS19) was higher than the percent of women in the American Astronomical Society (25%) and the International Astronomical Union (18%). The representation of women in Cool Stars as SOC members, invited speakers, and contributed speakers was similar to or exceeded the percent of women attending the meetings. We requested that conference attendees assist in a project to collect data on the gender of astronomers asking questions after talks. Using this data, we found that men were over-represented (and women were under-represented) in the question sessions after each talk. Men asked 79% of the questions at CS18 and 75% of the questions at CS19, but were 69% and 63% of the attendees respectively. Contrary to findings from previous conferences, we did not find that the gender balance of questions was strongly affected by the session chair gender, the speaker gender, or the length of the question period. We also found that female and male speakers were asked a comparable number of questions after each talk. The contrast of these results from previous incarnations of the gender questions survey indicate that more data would be useful in understanding the factors that contribute to the gender balance of question askers. We include a preliminary set of recommendations based on this and other work on related topics, but also advocate for additional research on the demographics of conference participants. Additional data on the intersection of gender with race, seniority, sexual orientation, ability and other marginalized identities is necessary to fully address the role of gender in asking questions at conferences.

-

Who asks questions at astronomy meetings?

S. J. Schmidt, and J. R. A. Davenport

Nature Astronomy, Jun 2017

Over the last decade, significant attention has been drawn to the gender ratio of speakers at conferences, with ongoing efforts for meetings to better reflect the gender representation in the field. We find that women are significantly under-represented, however, among the astronomers asking questions after talks.